Photo series — Toby Binder

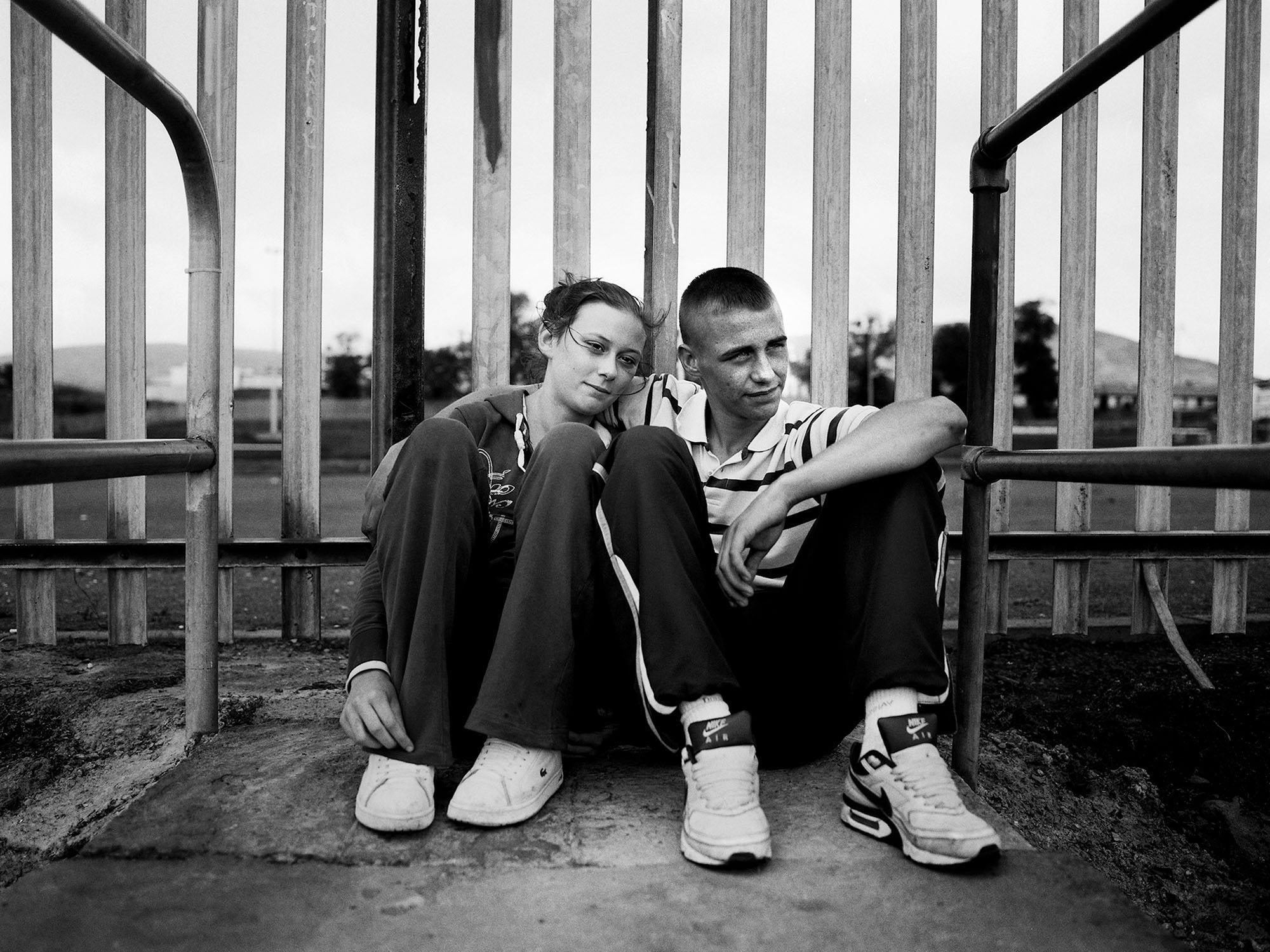

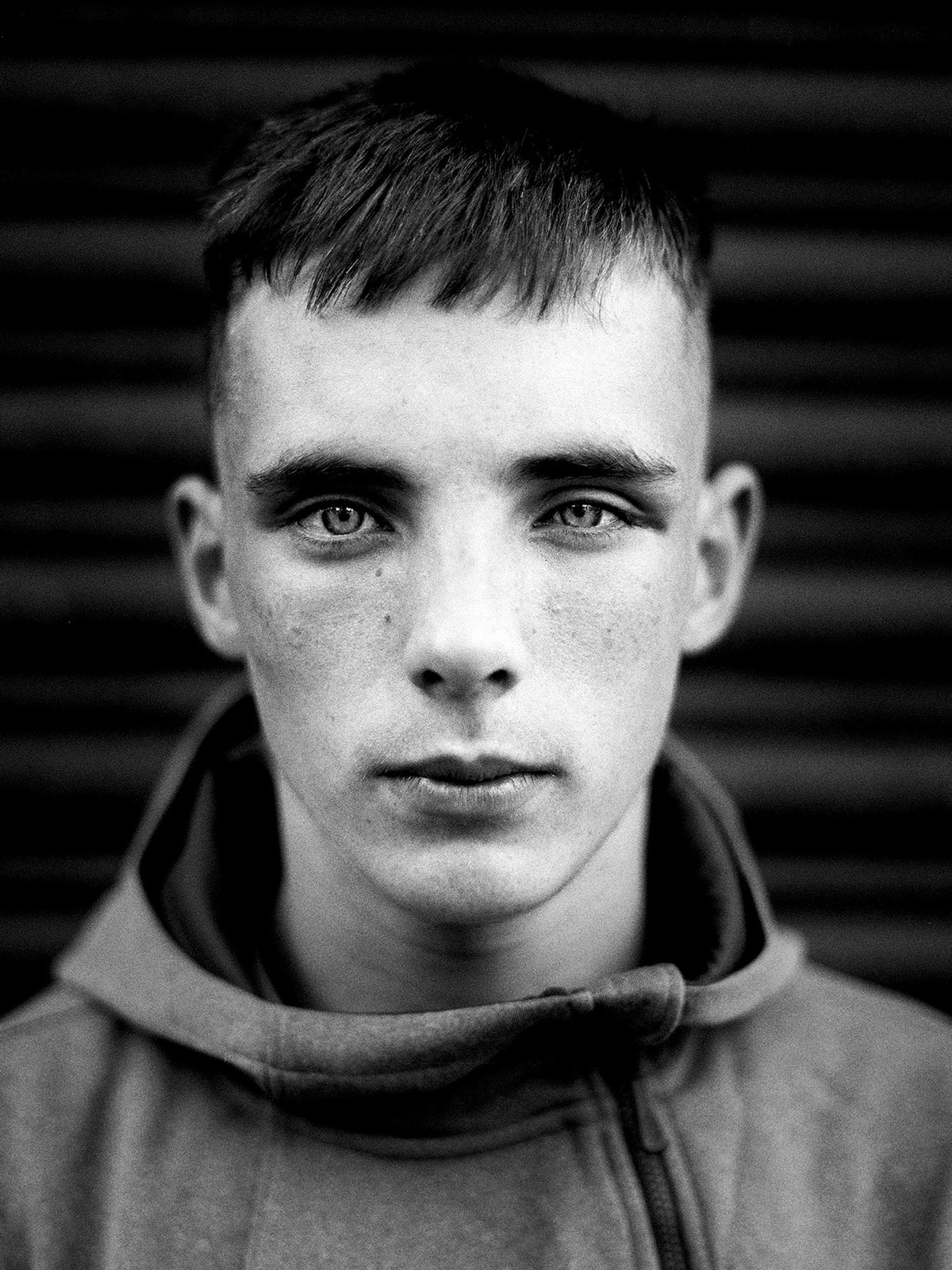

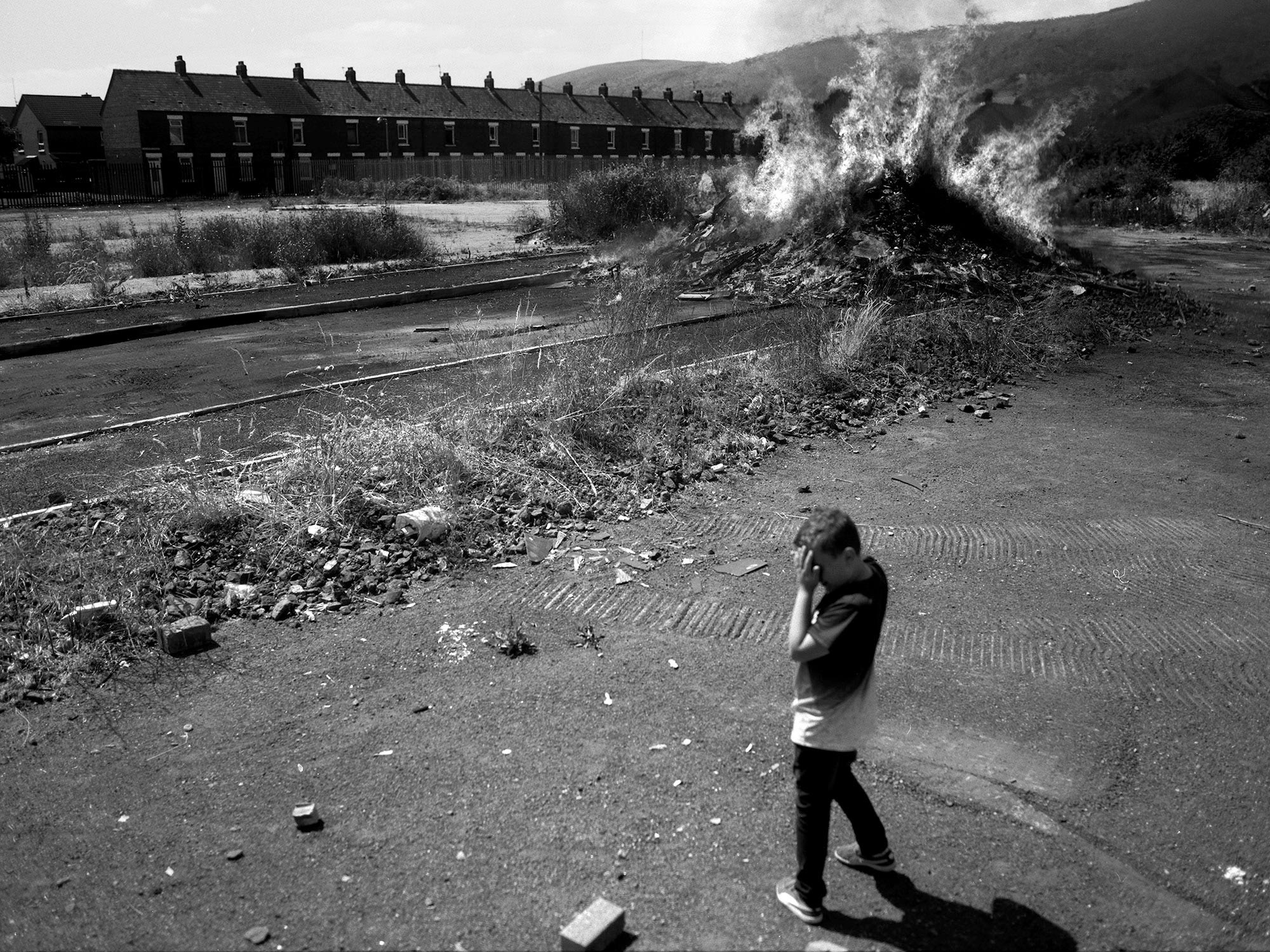

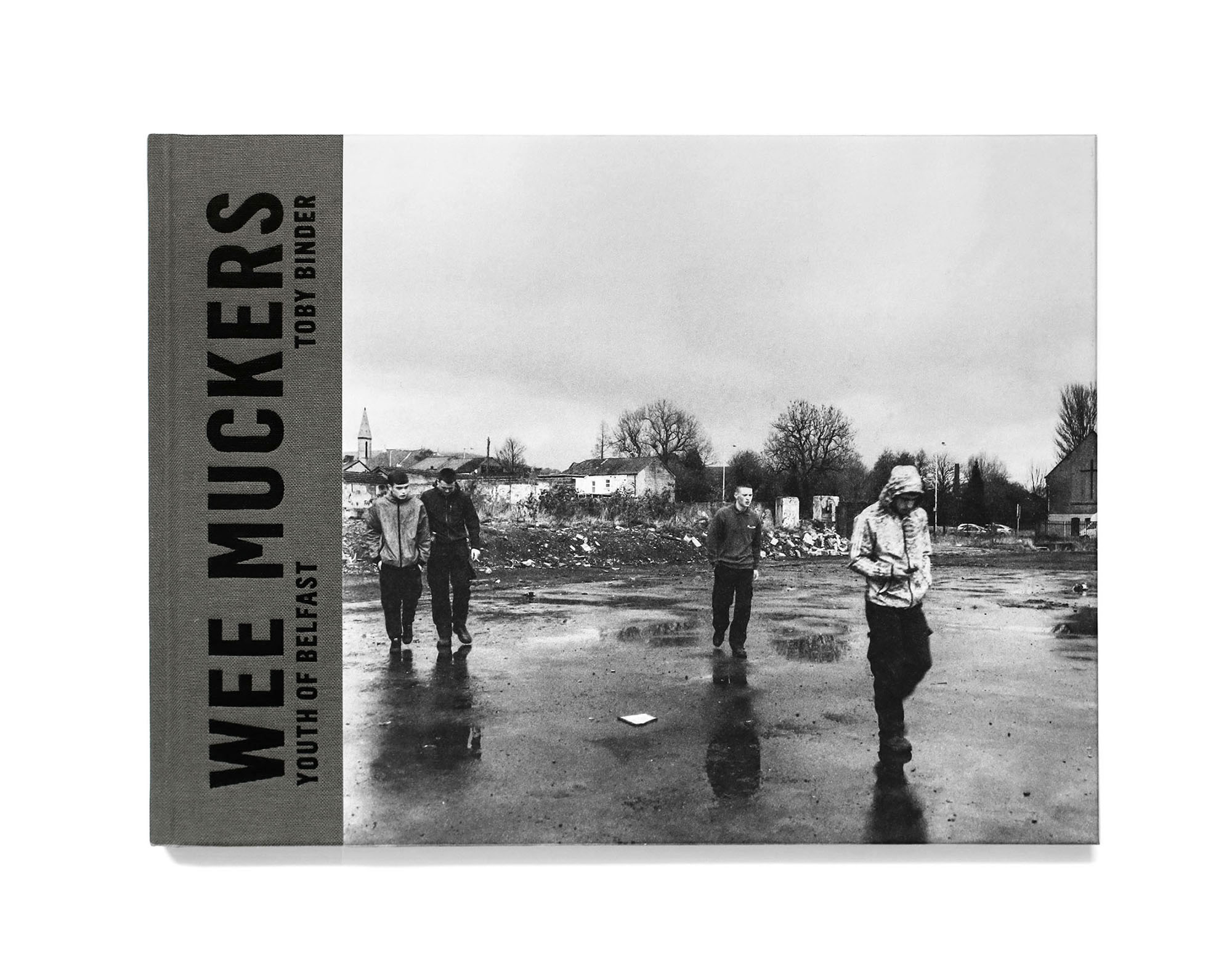

Wee Muckers

For his book »Wee Muckers – Youth of Belfast« photographer Toby Binder documented the everyday life of teenagers in Northern Ireland's troubled capital. Although the peace agreement between Protestants and Catholics dates back more than 20 years now, Belfast is still a place where it’s hard to grow up. On both sides.

8. Dezember 2020 — MYP N° 30 »Community« — Photography: Toby Binder

»If I had been born at the top of my street, behind the corrugated-iron border, I would have been British. Incredible to think. My whole idea of myself, the attachments made to culture, heritage, religion, nationalism, and politics are all an accident of birth. I was one street away from being born my ‘enemy’.«

— Paul McVeigh, Belfast-born novelist

Photographer Toby Binder has been documenting the daily life of teenagers in British working-class communities for more than a decade. After the Brexit referendum, he focused his work on Belfast in Northern Ireland where Protestant Unionists and Catholic Nationalists live in homogeneous neighborhoods that are divided by walls till today. But the problems they struggle with are similar—no matter which side of the Peace Walls they live on.

The open border between Northern Ireland and Ireland was a major condition for the Good Friday Peace Agreement 1998 — after 30 years of civil war. But after the Brexit in January 2020, and its actual implementation after the end of the transitional period at the end of the year, Northern Ireland also had to leave the European Union. There is great concern that a “hard” border could revive the Northern Ireland conflict. The sectarian separation also continues to this day. As a result, for the young generation there is no chance of growing up unencumbered in Belfast — on either side.

Armed conflicts are something that all teenagers in Northern Ireland today know only from the stories of the older generation. But if the border with the Republic of Ireland were to become a “hard” external border of the EU again, it is feared that this could be a blow to the still fragile peace process in Northern Ireland.

The majority in Catholic-nationalist neighbourhoods voted to stay in the EU, most people in Protestant-loyalist neighbourhoods voted for Brexit. This referendum result made very clear how different the vision of Northern Ireland’s future is in these two camps and how deep the resentment of the past lies.

The economic disadvantages of leaving the European Union without follow-up economic agreements are likely to affect mainly socially deprived neighbourhoods. It is therefore feared that the violence in the traditional working-class districts — the former strongholds of the IRA on the Republican side and the UVF on the Loyalist side — could flare up again.

#tobybinder #weemuckers #belfast #community #mypmagazine

Photography & text: Toby Binder

Toby Binder: “Wee Muckers – Youth of Belfast”

Text by Paul McVeigh

Designed by Birthe Steinbeck

Hardcover, 24 x 17,5 cm, 120 pages, 87 duotone ills.

ISBN 978-3-86828

signed and numbered (500)

€ 35