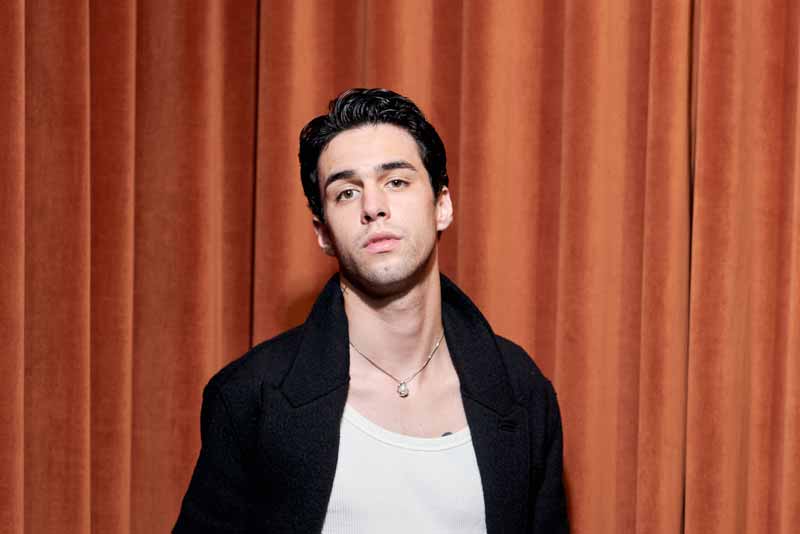

Interview — Ólafur Arnalds

»People don’t know what silence is anymore«

The Icelandic composer Ólafur Arnalds achieves what seems like a contradiction: With his opulent, sophisticated, and sensitive music, he leads his audience to a moment of total silence. This is also urgently needed, as our society seems to be increasingly losing its sense of stillness. We met him for a very personal interview about elitist art schools, the need to protect himself from other people’s emotions, and the insight that there are more important words in his life than »music.«

23. Oktober 2022 — Interview & text: Jonas Meyer, Photography: Maximilian König

The world is a mess. Glaciers are melting, species are dying out, oceans are polluted, and there are fewer and fewer places on the planet that are completely dark at night. If that wasn’t enough, Earth has another problem to deal with: noise pollution. According to researchers, the constant presence of various noises caused by industry, mining, forestry, and transportation are increasingly affecting the health of flora, fauna, and us, the humans.

So, it’s high time to do something. If it can’t be done on a large scale first, maybe at least on a small one—as practiced by Ólafur Arnalds. The 35-year-old musician and producer from Reykjavík, Iceland has made it his mission to help people regain a real sense of silence through his music.

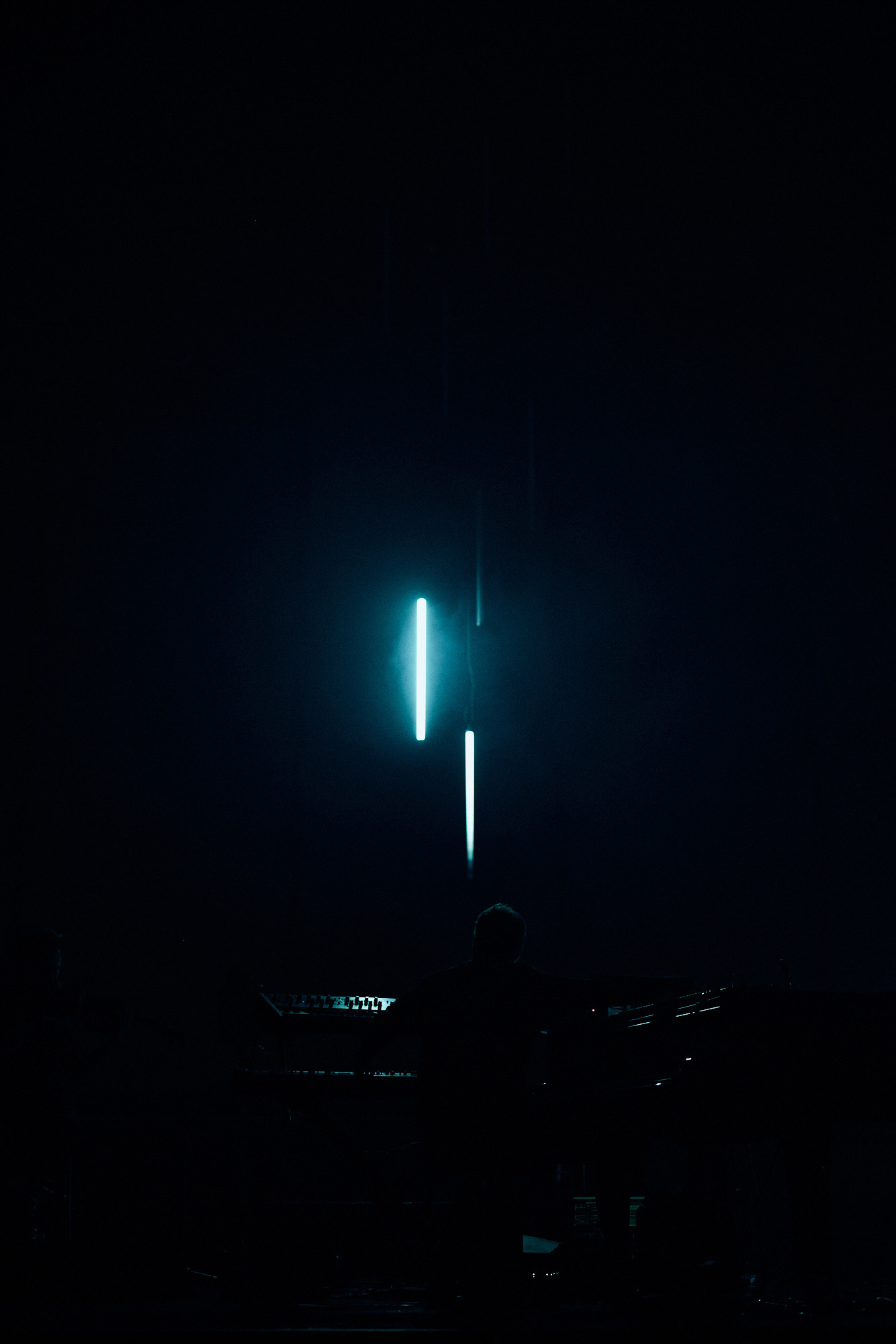

What sounds like a contradiction in words can be experienced live at one of his shows, such as his performance at the Tempodrom venue in Berlin a few weeks ago. Over the course of the concert, he successively reduced the volume, speed, and intensity of his music until at the end he creates what he has been working towards for almost two hours: total silence—at least when the audience joins in. Because total silence is something that not everyone can handle. The night before, when singer-songwriter Ry X asked for a short moment of quiet and meditation in the same place, here and there people could be heard laughing, whispering, or clearing their throats.

But Ólafur Arnalds seems to have tamed his crowd. Before that, he gave them an entire evening filled with ecstatic soundscapes and sensitive melodies, presenting mainly his newest album, Some Kind of Peace, which he released in 2020. A few hours before the show, we had the chance to meet him backstage for an in-depth interview.

»For me, an album just doesn’t exist when you don’t play it live in front of people.«

MYP Magazine:

Ólafur, you are currently touring with your album Some Kind of Peace that you released in November 2020, which is kind of a time gap caused by Corona. Did your feeling for the songs and the way you play them change during that time?

Ólafur Arnalds:

Yeah, it’s quite funny because we didn’t really play them at all after recording. It feels a little bit that the album had disappeared in the meantime. For me, an album just doesn’t exist when you don’t play it live in front of people. That’s what brings songs alive. So, I had almost forgotten about these songs, also because I’ve been working on so much other stuff for the last two years which made that album lie far in the past and never gave it the chance to become deeply ingrained in me.

MYP Magazine:

That means you had to rediscover these songs…

Ólafur Arnalds:

Exactly. And this was fun—and a little difficult because I felt that most of my time was spent really learning the songs from new instead of developing them as I usually do for live shows after they have been released. But this time it was like I had to learn how to play them because I’d forgotten it. (smiles) But it was really great to come back to these songs and it feels amazing to be able to finally play and develop this music. Being on the road right now, we constantly play around with these songs, change them and work with them more and more.

»I’m writing visually, but in the sense that I’m looking at the notes on my paper or screen.«

MYP Magazine:

Listening to your music, I often have to think of these kinds of situations when two people meet, especially in the first seconds when a melody develops in the space between them. It’s like you could feel this space. Do you yourself have certain visuals in mind when you start writing a song? How does a melody find its way out of you?

Ólafur Arnalds:

It happens, but usually not. Of course, sometimes I’m thinking of specific emotions, people, or things that happened when writing a song. But most of the time I’m really just in the melody itself and it happens quite visually for me in the sense that I write it down. I work on a computer, often using MIDI sequencing to write string arrangements, for example. I think what you’ve heard when you introduce a melody, it sounds like it’s introducing people a bit and then later it feels like you know it, I guess that comes from me often writing in a visual way, looking at stuff and then I can see the patterns. Then I can kind of break them apart, maybe write backwards in a way. I often start with the main part and then I write the intro. And then I can take little bits of the main part and place them here and there. So, you feel like the melody is broken in a way when you first hear it, and later it comes together. I think that’s very much happening because I’m writing visually, but in the sense that I’m looking at the notes on my paper or screen.

»I still have a lot of empathy for people’s emotions, but I just try not to put that weight on my shoulders.«

MYP Magazine:

Your music touches many people across a broad spectrum of fundamental emotions. What level of responsibility does that bring for you? Do you sometimes even feel it as a burden to make music that has such an emotional impact on its audience?

Ólafur Arnalds:

Sadly, you have to disconnect yourself from that. If you’re empathetic enough that you feel the emotions of every person who sends you a letter or a message, or who you see in the room, then it becomes a burden. It’s not possible for a human to take all that on their shoulders. It would destroy you, and I am not an exception to that. That’s often why some people who are much more famous than I am have such great success—because they are distancing themselves much more from the public, to not let people’s emotions get to them. If you touch someone in that way, you don’t know them. If you’re going to take all of them on, it’s very heavy. I used to do it, I used to take it all on when I started to make music. I suddenly seemed to feel what everyone else was feeling, and I had to really learn how to distance myself from that. That doesn’t mean that I don’t care about it. I still have a lot of empathy for the people’s emotions, but I just try not to put that weight on my shoulders.

»I felt I had to protect myself, in a way.«

MYP Magazine:

Do you remember a specific note or message where people let you know about their emotions?

Ólafur Arnalds:

Yes, I remember many. I’ve met people with terminal illnesses and with whom I started exchanging letters, for example. They told me that my music was helping them going through something. Especially earlier in my career I always felt that I had to respond to those kinds of messages. I felt a responsibility to respond to a person who pours their heart out to me. So, I would make friendships with these people, and of course, it would destroy me one day when they pass away. That’s why I felt I had to protect myself, in a way.

I always remember this one person who, a long time ago, sent me a letter after a show. She had been very depressed and ended up in a hospital after a suicide attempt. In that moment, she was just angry because her attempt didn’t work. She had thought, “I’m gonna get out of here, so I can try it again.” One day her friend brought in an iPod—as I said, it was a long time ago (smiles)—and the only thing on it was my album. After listening to that, she said that she felt for the first time a willingness to live. She told me that there was a particular song she was listening to again and again that gave her the hope that there actually is some beauty in the world.

»It’s our responsibility as musicians to spread this gift that we’ve been given to the world.«

MYP Magazine:

If you can save just one life, it’s already worth doing the job…

Ólafur Arnalds:

Exactly. A year or two later she was healed, had a new job, was living a new life and finally came to my concert. That was the culmination of her personal journey and that’s when she sent me that letter. It was a very beautiful thing to receive and think, music actually can save a life. Even though I talked about the burden of feeling a personal responsibility for every human being who contacts me, I also do feel that it’s our responsibility as musicians to spread this gift that we’ve been given to the world—because it might do some good. I really believe music can change the world. It’s so cheesy, but music is the place where you offer kind of a neutral song—like Switzerland—and you can see the world from different perspectives because music has a language that can say something we cannot say with words. I think that’s more important than ever in these times—personally, emotionally, but also politically. That’s the responsibility I feel and that’s our mission here.

»People don’t know what silence is anymore.«

MYP Magazine:

On our planet, it‘s very hard to find a place that is completely dark at night—because of the light pollution. And it’s pretty much the same with noise. Would you say that, with your music, you can create silence where usually there is none?

Ólafur Arnalds (smiles):

That’s something we play with as an instrument; we love to play with the silence of the audience. One of our biggest missions every day is the walk around the venue to find everything that makes a little bit of noise—because people don’t know what silence is anymore. They just don’t know. When they come home, they think it’s silent there. But it’s actually not. The air conditioner is on or the refrigerator, for example. That’s why few people have truly experienced complete silence in their lives.

MYP Magazine:

I can imagine some people are also afraid of total silence. Last night at the Ry X concert, for example, he asked the audience for a common moment of silence and meditation. A lot of people tried it, but there were also some that were just not able to pause and remain in complete silence. They coughed, started whispering after a few seconds, a few made jokes…

Ólafur Arnalds:

I think it’s difficult to force people into an uncomfortable situation. You have to create the silence for them. That’s why we try to leave the music successively: The way the set list and everything is built is aiming towards this final point at the concert, which is complete silence. It happens so gradually and so slowly that people don’t really realize that they are being tricked into complete silence. (laughs) But at the end, we often have 20, 30 or even 40 seconds of complete silence with 3,000 people in the room. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

»This possibility of everything is not always helpful—because when you can do everything, where do you start?«

MYP Magazine:

Since you’ve been making music, film music has always played an important role in your artistic work. Why are you personally so fascinated by this genre and by creating music for series and movies?

Ólafur Arnalds:

It’s mostly the process of it. When I do my own albums, I always start with a completely blank slate. In theory I could do anything. I could do a hardcore metal album if I wanted to, whatever. But this possibility of everything is not always helpful—because when you can do everything, where do you start? You always have to start with creating some boundaries, like “I’m gonna make a piano record” or “I’m gonna start with a piano.”

The beautiful thing about working for films is that there is already a boundary. There is a character, there is a story, there is a script, there might even be a cinematic style already so you can have a feeling for the show, and often there are some specific wishes of the director. They usually come to you and say: “I want it to sound like this and this.” It’s nice to work within those limitations because actually, you become more creative by that. The more limitations there are, the more you have to fight and push in new directions to find a way to create something great within those boundaries. This is what I actually enjoy. And it helps me when I come back to my own albums because I’ve usually learned something new through this process. It often pushes me somewhere I hadn’t been going otherwise.

»There was a moment when I felt that I had to make sure that people see me and my music in a more positive light.«

MYP Magazine:

One of your most famous film compositions is the soundtrack for the crime series Broadchurch, in which the murder of a little boy is investigated. It seems that the music and the series are firmly intertwined. Did you ever worry that this symbiosis would rub off on your other work? That people would always associate your sound with such a dark story, and you would need to protect your music?

Ólafur Arnalds:

Worry is not a feeling that I have in my vocabulary. I don’t worry about anything. It’s weird, I didn’t really understand the construct of worrying until I met my girlfriend. She worries all the time. But I’m raised differently, I guess. I’m always the opposite of it, which for me is obliviousness. (smiles)

I remember one time I was watching the Icelandic news and after that a 60-minute-show where they used to focus on one subject. It was about date rape drugs, a really dark and horrible subject, and the whole show was underscored by my music. I thought: “Oh shit, I have to get out of this. That’s going to be the music people will go to when they talk about horrible stuff.”

So, yes, there was a moment when I felt that I had to make sure that people see me and my music in a more positive light. I do make an effort! If you watch my music videos and all the content we produce, it’s all way more positive. It is rare that you see something really sad happening. I always think—and that may come from my experience in film scoring as well: If you have a sad scene in a movie and you put sad music under it, then you have cheese, you have kitsch. You need to be a little more creative with how to put these things together. You could combine sad music with something less obvious and more unexpected—like in the German film Victoria, for example. There’s a great party scene where the main actress is in the club. Suddenly all the music goes out and there is this really sad piano coming and everyone is partying. That’s so interesting!

»In music—and in arts generally—doing it wrong is usually a good thing.«

MYP Magazine:

I found out that, when you were studying composition at the Arts Academy, you had to fight battles with your teacher over and over again. You had a teacher who thought that everything that you thought was right, was wrong. Do you feel anything like satisfaction today? Or do you think that these battles helped you to develop your very own musical style in the end?

Ólafur Arnalds:

The latter might be right—because I’m very stubborn. I think when somebody says “You’re doing it wrong,” then I double down and do it even more like that. In music—and in arts generally—doing it wrong is usually a good thing. So, it did push me, it made me want to explore even further what I was beginning to explore. Don’t get me wrong: I understand teachers. Their role is to introduce you to new things, not to what you already know. But I didn’t like the vibe there. In many art schools, when you talk about classical music, it can be a little elitist in that sense…

MYP Magazine:

But wouldn’t it be in the interest of classical music if it were more inclusive and many more people engaged with it?

Ólafur Arnalds:

Right, that’s what I think. But a lot of people in classical music think differently. They think it should be exclusive. They like their little club, you know? (laughs) But at the same time, you have these orchestra marketing directors who try to appeal to the public with some horrible ideas.

»I think my role is more to poke and annoy people a bit—I enjoy that in a sense.«

MYP Magazine:

Have you ever met that art school teacher again?

Ólafur Arnalds:

Yeah, we meet from time to time. There aren’t any hard feelings. It’s just a nice story today and he understands. When I met him one of the last times, we had a few drinks at a music industry event a couple of years ago. At that time, I was thinking about going back to school to finish my studies—because I was having imposter syndrome. Although I was already successful, but I felt I didn’t deserve it because I thought I didn’t know shit about anything I was doing. I continuously said to myself: “Why I am here? I have to finish my studies so I actually can get good at composing.” I told that to my former teacher and said that I really wanted to go back. And he just answered: “Why would you? Everything is fine.”

MYP Magazine:

I can imagine that these elitist people you talked about are also strictly against the combination of classical music with electronic music or against the use of high tech. You, on the other hand, seem to be eager to unite these worlds. Would you say that you can continue to tell the history of classical music with this approach?

Ólafur Arnalds:

I used to think so and it used to be a part of my mission. But today, at this point, I’m like “Fuck it!” If they want to kill themselves like that, they can die. I’m not the savior of classical music, I don’t want to be that and that’s not my job, also because I’m not from classical music. If someone needs to save classical music, it needs to be a person who grew up in classical music, who knows classical music and who can play classical music. That’s definitely not me. I think my role is more to poke and annoy people a bit—I enjoy that in a sense—and to try to open some doors. Then hopefully someone else can follow me through these doors. That would make me very happy.

»What if I could create software that would think like software but play like a human?«

MYP Magazine:

You invented a special form of a self-playing piano steered by artificial intelligence. Two of them are currently accompanying you on your tour. Why did you feel the need for that?

Ólafur Arnalds:

The idea came from a time when my hand was injured and couldn’t play the piano very well. So, I was looking for creative ways to create piano sounds because when a piano could play itself, I wouldn’t need my hand. Of course, my hand healed after some time, but this funny idea was actually very interesting and triggered a sequence of events. I wondered: What if I would think not only about what we can do physically, but also what our brain can do? What if I could create software that would think like software but play like a human? The results would be something I would have never thought about because even if I myself would play like this, I could never move my fingers in that way. So, an idea was born to discover some new sounds and melodies that I wouldn’t have found any other way—and that pushed the boundaries of what I’m doing a little bit. That’s good because I don’t want to be too stuck in piano music, neoclassical music or whatever you want to call it. I want to be bigger than that in a sense.

MYP Magazine:

Can you explain how exactly this machine works?

Ólafur Arnalds:

It works through MIDI, a very simple signal protocol that’s often used in music. On my grand piano I have a sensor that captures what I play, for example a C major chord. It sends that chord to the software which distributes it to two self-playing pianos enriched by generative rhythmical textures that are based on the melodic material that I’m creating. By that, I myself can control the parameters of the textures, such as fast or random, or slow and rhythmic, or heavy, or light, which means it’s not completely an AI thing. It just accompanies me in a way.

»Music is my whole life, but it isn’t an important word as such.«

MYP Magazine:

Last year you released a track called “Saudade.” In the Portuguese language the word Saudade describes a very special emotion, which could be described as a mixture of sadness, wistfulness, longing, or gentle melancholy. How did you find that word? And why did you want to dedicate a song to it?

Ólafur Arnalds (smiles):

The word came to me on tour. We have something of a quirk which we call “word of the day.” Every day in different cities we come across so many signs, instructions, and words in the language of the particular country, that Àrni, one of our team members, puts up one sign which includes the word of the day. One day he proclaimed Saudade and has taught us about its meaning—a really fantastic word that I’ve had in my mind ever since. And then I had this song and just needed a title. It’s not any deeper than that. (laughs)

MYP Magazine:

Speaking of words: The philosopher Albert Camus once listed the ten most important words of his life—Les dix mots préférés d’Albert Camus: the world, the pain, the earth, the mother, the humans, the desert, the honor, the misery, the summer, the sea. What are the most important words of your life?

Ólafur Arnalds:

It’s a really interesting question because there are definitely important things that I do in my life, but the word for these things might not be that important—like “music,” for example. Music is my whole life, but it isn’t an important word as such. I don’t say that word, I just do it. But to name a specific word: One of the most important things in my life is perspective. There is a lack of perspective in the world, that’s why it’s something to fight for. In addition, important are empathy, tolerance, and kindness. You can see where I’m going with this, I was raised by two hippies. (smiles) But these are the things that really stay on my mind.

More about Ólafur Arnalds:

Photography and videos by Maximilian König:

Interview and text by Jonas Meyer:

Editing by Benjamin Overton: