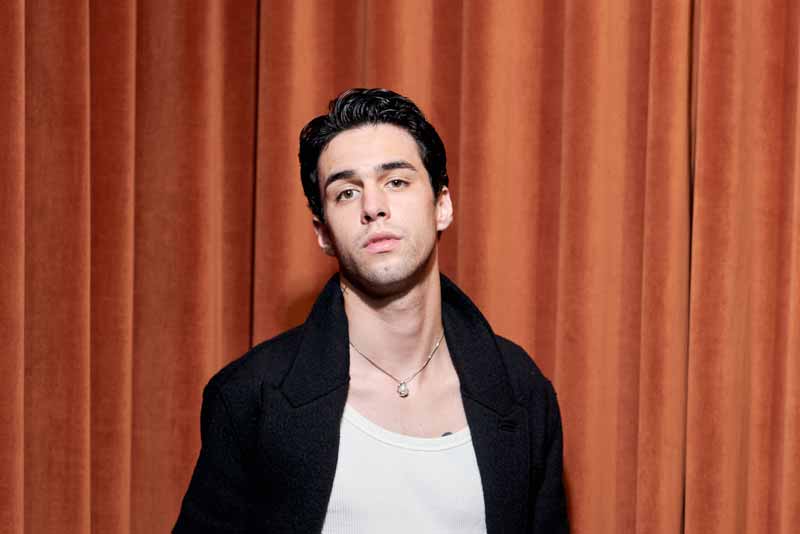

Interview — Ryan Fitzgibbon

Exposing The Flaws

Grown up in suburbia, Ryan Fitzgibbon left as soon as he came out of age, to explore his queer identity and his connection to verbal arts. By publishing a lovely magazine called Hello Mr., he speaks directly to the experiences of a modern, gay audience.

29. November 2015 — MYP N° 19 »My Protest« — Interview: Jonas Meyer, Fotos: Franz Grünewald

Is man not a strange creature? It doesn’t matter if he’s going out on a date, applying for an apartment, or interviewing for a job, he will go to any lengths to be considered first choice: Pull in his stomach, feign a working relationship, and demonstrate absolute will to succeed. Perfection is the price of entry to the pantheon of winners. Therefore most people keep the following answer up their sleeve for the inevitable, hackneyed question, regarding their greatest weakness: „I’m too much of a perfectionist.“ But, come on – really?! Would it not be much braver to actually stand by one’s flaws, and share in a meaningful revelation of true humanity?

A Wednesday morning in late summer. We are seated across from Ryan Fitzgibbon in front of one of the storied bookstore Walther König’s massive plate glass windows, not far from Hackescher Markt. Fitzgibbon is the founder and editor-in-chief of Hello Mr., a publication that bears the unassuming subheading about men who date men, and has garnered much attention on the international magazine market since hitting stands for the first time two years ago. Ryan is in town to visit the printing house that he has worked with ever since the magazine’s first issue.

Print? That’s right. Even in this digital age of online publication, print refuses to die. Just last year, Fitzgibbon proved that the medium can even flourish: Barnes & Noble, the United States’s largest bookseller, decided to include Hello Mr. on the racks of a number of stores. The achievement is all the more impressive, considering the conservative mores that still dominate wide swaths of the US.

The light is perfect for our shoot, so we cross the canal to explore Berlin’s famous museum island, a unique ensemble of historical buildings that was declared a UNESCO world heritage site in 1999. Crossing Friedrich’s Bridge, the first museum we stop at, the Old National Gallery with its collonated atrium, lies only a couple of minutes walk from the bookstore.

It strikes us that the location is impressive not only for the pomp and splendor of the century and a half old architecture, that required costly restaurations after 40 languorous years of GDR rule, but also for the scarring on the facades, left behind by bullets and fire. These footprints of war evoke the the drama played out here in the spring of 1945. It was a wise decision to leave them untouched during the buildings’s restauration. Any attempt to expunge them would have robbed the location of its authenticity and integrity – its very soul.

We linger a moment among the columns before moving on to the Old Museum and Lustgarten, then further down Bode Street towards the German Historical Museum, a modern building of glass and steel. It would seem excessively sterile, were it not for a white bench in front of the entrance. On the left-hand side of the backrest the words ‘Homosexuals Only’ are stencilled in black letters, on the right a single word – ‘Only’. The bench belongs to Homosexualität_en, a special exhibition on 150 years of homosexual history, politics, and culture in Germany.

Jonas:

As we can see on your Facebook and Instagram profiles, you used to travel a lot to many different places all over the world. Your life started out in Michigan. What was it like growing up there?

Ryan:

Where I grew up was very suburban, and pretty average. Not very small but small enough that I felt like I needed something more. I think that’s why I have had the travel bug for such a long time. I just wanted to explore outside of what was there. I think that’s very common for a lot of people. Not just young creative people but anybody who grew up in a small town. After I studied graphic design in Michigan I moved out to San Francisco for a job, and that job was based on doing research in other countries, so I was traveling a lot – mostly with a design consulting agency called IDEO I worked for. I would go to learn about other people’s behaviors and interests in different parts of the world.

Benedict:

There’s a book by James Franco, called „A California Childhood“. For people who know the US only through the filter of television and film, this book seems to represent the prototype of an ordinary childhood in your country. It’s full of photos showing grad nights, volleyball teams, cheerleaders, yearbook portraits, roller blade tours and paddle ball matches on the beach. Do you feel like you had a „typically American“ childhood, or is there no such thing?

Ryan:

I think what is depicted in popular culture is typical, and relatable to my experience growing up. I imagine that your idea of a typically American childhood is probably pretty accurate, especially in a suburban area, like where I grew up. There’s nothing too shocking there.

Benedict:

Would you say you had a good time?

Ryan:

Yeah, where I grew up made it very easy for me to aspire to more, and do more. The people I grew up around were all very supportive of what I wanted to do. At the same time they encouraged me to try a lot of different things, or made it feel like it was an obligation to play a sport, to be a part of boyscouts, to be a part of art club, and just have a lot of extracurricular activities at all times. That made me ambitious to be involved in a lot of things but then once I started to make my own decisions, I focused more on art. From there I got into design.

Jonas:

Was there anything, or anyone, specific that caused you to decide on design?

Ryan:

When I was in high school I studied art, and got involved with the school newspaper, and was encouraged by my art teacher to be a design editor. I fell in love with it, and after working for a year at the newspaper I decided to try a commercial art graphic design class where we made t-shirts and posters.

Jonas:

It’s amazing that you had that at school.

Ryan:

Yeah, at the age of seventeen. I was getting into graphic design much earlier than most other people discover it. After high school I got into a design course at university, but it was definitely my art teacher who got me to try out the newspaper that started the whole thing.

Jonas:

Are you still in contact with her? Does she know what you do now?

Ryan:

We hadn’t spoken in a while actually, but I recently received an enthusiastic email from her saying that she found my photo in a copy of a magazine called Hello Mr. during a trip to Barnes and Noble. Such a nice surprise for both of us.

Jonas:

I think it must be a great feeling for teachers to know that what they try to pass along to students can lead them to success later in life.

Ryan:

Yeah, I think that’s what makes teaching so valuable.

Benedict:

Do you remember any of your childhood idols, or heroes?

Ryan:

I know I had people I looked up to outside of family and personal life. Once I really got into design, I started to follow all of the big designers and studios. I admired not just the craft, but also the acumen needed to run a design house. I thought that was the path I was on. I wanted to eventually run my own studio. In a way I still consider myself a creative director, although I primarily work as a publisher, producing the magazine Hello Mr. and different experiences around that magazine. It’s a much broader set of responsibilities than I thought I would assume when I was studying.

Benedict:

In 2009 you moved to San Francisco, right? What led you to go there?

Ryan:

I finished my bachelor’s degree in fine arts at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, exploring the value of design for my thesis. IDEO was a big influence on my research, and I referenced a lot of Tim Brown and David Kelly’s books on innovation and design. I really dove deep into the concept of design thinking, and decided that I would apply for an internship there. I got it, and moved there for the job.

Benedict:

So it isn’t as though you moved there with no idea of what you would be doing.

Ryan:

Right, I moved there with a plan. That was the last move I made that was really for something specific. When I left San Francisco, I moved to Australia with no real idea of why I wanted to go, or what I would be doing there. My move to San Francisco was positive in the sense that it got me started but I soon realized that I wanted to make decisions and moves for myself.

Benedict:

It sounds almost like a personality change, going from having a plan for everything to the exact opposite.

Ryan:

Like I was saying before, I felt like I was on a path to be a traditional graphic designer. My volunteer work for AIGA, the professional association for design, connected me to a lot of different networks, and lined me up to go down that path. When I realized that I wanted to explore something more personal, and not repeat a path that many other people had already traveled before me, I had to start making decisions that didn’t have clearly defined consequences.

Launching into my year in Australia was a bit unconscious in the sense that I didn’t know what I was doing. As soon as I made the decision, and started to figure out the answer as to why the decision was made, it all came together. Of course other people have started businesses, and other people have started magazines, but the path is not laid out for you. That’s also when I started to figure out where professional and personal interests could overlap.

Jonas:

It seems as though you started to design your own life.

Ryan:

Kind of.

Jonas:

To my mind there are two components of design – the aesthetic and the function. Both have to work together. In life it is similar.

Ryan:

Right.

Benedict:

The company you worked for in San Francisco operates out of Palo Alto. Is that where you lived?

Ryan:

I lived in San Francisco. They have an office there as well, although I did in fact mostly work in Palo Alto.

Benedict:

We were there in April. It was very calm and down to earth, like your typical small town. It was hard to fathom that it is the digital center of the world.

Ryan:

It’s a bubble. The perfect little city.

Jonas:

I heard it’s one of the most expensive places in the world.

Ryan:

That sounds about right.

In Silicon Valley there is obviously a sense of competition, and motivation to have the best ideas, but there is still a sense of community, and building on one another’s ideas.

Benedict:

Did you feel inspired by the spirit of Palo Alto?

Ryan:

You do, in an interesting way. It’s different from New York, where you feel encouraged to help drive the hustle and work harder. In Silicon Valley there is obviously a sense of competition, and motivation to have the best ideas, but there is still a sense of community, and building on one another’s ideas. There’s still a lot of collaboration and cross-polination. That’s motivating and inspiring. In New York there’s more of an interest in exchanging services and ideas for personal gain, while in Palo Alto it feels like people are interested in improving the world.

Especially at IDEO – that’s a very supportive community that emphasizes the value of sharing your ideas, and not being precious with a concept. A concept is not going to be as good in your head, as it is on paper, where someone else can add something to improve it, or provide feedback.

That’s where the concept of rapid prototyping comes into play, which is just the idea of building something fast, tearing it apart, and rebuilding it. Through that process you make something stronger and more viable.

Jonas:

It’s strange to see that Palo Alto is not this artificial city that one is tempted to envision it as – you don’t have the ivory towers you would imagine there. The town has good vibrations. What made you want to leave, and why did you choose Australia?

Ryan:

When I was with IDEO in the Bay Area, I was only in the Palo Alto offices for about a year and a half total. The rest of the time I was traveling. I spent five months in Singapore, Brazil for about a month, India for three weeks. One of my assignments was to Australia, and I was in Melbourne for about a week. I really fell in love with the city when I was there in 2011.

Anyway, I decided to leave IDEO before I decided to go to Australia. Melbourne was in the back of my mind constantly, but it didn’t become a concrete option until I visited Italy in 2012 while I was trying out for Benetton’s Fabrica Program. It’s an incubator research and development facility in Italy run by United Colors of Benetton. They bring people who are younger than 26 in for a year-long residency, and I was there to try it out for two weeks. I was in the graphic design department, and a lot of the people there were Australian. I thought it would be cool to explore why the design I was interested in revolved around Australian design sensibility. I started following a lot of the designers on twitter, and reached out to a couple of them.

Australians, especially in Melbourne, still support print magazines, whereas in Silicon Valley print magazines were quote unquote dead. With those things in mind, I decided it would be worth a try to go to Australia after I was rejected by Fabrica.

Benedict:

Was it a clear idea you had, to make a magazine? Normally, when people decide to make a magazine, there is usually a turning point. I’m trying to figure out how this desire came about.

Ryan:

The idea started in the last year that I was living in San Francisco. I was 23 at that point, and had been out of the closet for about two, maybe two and a half years. After moving away from Michigan I suddenly found myself surrounded by people who understood me, but at the same time I couldn’t relate to the visual communications, designs, and branding that were quote unquote gay, and what was marketed as gay. As a designer it felt like an interesting challenge to come up with a new brand that was relatable to me, and could fall under the label gay. In the beginning it was just a blog that I used as a platform for this rebranding. I wanted to share stories that I could relate to, and that my friends could relate to.

When I moved to Singapore for a bit, for work, it became apparent that the community I was comfortable with in San Francisco was the complete opposite in the rest of the world. I would spend my days in Singapore at cafes and book stores reading magazines, but I didn’t find any gay magazines there. I thought that the appreciation for print in other parts of the world meant that the blog I was running, called Hello Mr., should really be in print, so people could have something to buy, bring home, and read. There’s something about the design of Hello Mr. that is relatable to people.

I always loved magazines, and I knew that I wanted to do print design ever since I worked for my high school newspaper. It wasn’t until I realized that I could have more of an impact with a magazine on a shelf, sitting next to GQ and other straight publications, that I gave it serious consideration. It still needed to be about men who date men, and it needed to be confident about that.

Jonas:

Help me to understand this better: You felt like the public perception of gay life is not an accurate reflection of the reality? That it isn’t always about partying, flamboyant dress, and other gay stereotypes.

Ryan:

It’s a mix of that. Of course there are symbols and representations that I participate in and identify with. On a larger scale however, I recognized that media representations were not evolving with the new generation growing up around them, and being more accepted by society.

Jonas:

Because it’s much more normal than people think?

Ryan:

Right. So I think that there is still great value in having a range of ways that we express who we are but there wasn’t anything serving the target audience I wanted to address.

Benedict:

So Hello Mr. is a way of telling the world who this new generation of gay men really is?

Ryan:

I feel it’s more a way of giving people who haven’t recognized themselves in a magazine before an opportunity to connect to other people who feel the same way. Not necessarily to redefine what it means to be a gay man, because there are so many different versions of that anyway, but to showcase a portion of that group.

Benedict:

It’s a very personal magazine. You have people sharing parts of there lives that are so intimate that it resembles a mental undressing. That’s the thing that really differentiates the brand from others.

Ryan:

That’s a good comparison. I speak a lot about the act of vulnerability, and exposing our flaws. If we expose our flaws, and what makes us similar to everyone else – we all experience heartbreak, we all have issues – I think that can connect us. More than describing what makes us different. I think what a traditional gay magazine of the past represents is the idea of a perfect image, be that the perfect body type, or a perfectly happy couple. I don’t think that perfect ideal is as relatable as something that is honest and real. That’s what I wanted to show – body types that aren’t perfect. I want to break down the barriers that portray us all as successful and happy. Often we are, but we still have flaws and edges.

Jonas:

A person who is very special to me once told me that life is just about sharing, and the concept of our both magazines underlies that attitude. With MYP, we see that people have a need to share, and to talk about their inner feelings and their thoughts. We also found out very quickly that it is hard to find people who are willing to open up. Was it hard to find people for your first issue?

Ryan:

It was actually incredibly easy because the gay audience I was reaching out to were ready for this platform to share their voice on. Initially I didn’t work with a lot of big names either, so I looked for stories that were real, and relatable, and honest… and imperfect. So we worked with people who had never written before, and helped them tell their stories. They made it so much more important because they were so interested in sharing. Of course not all of them were hitting the mark but that was just because it hadn’t been done up to that point. Now there is a clearer understanding of what we do, so it’s much easier to give feedback.

Jonas:

I’m sure you get very personal stories when people send in their submissions, and you probably have to make hard choices about which texts to take. How do you achieve personal distance to the things people send you? From personal experience I can say that some of the submissions we receive deal with matters of abuse that are extraordinarily hard to read. It’s difficult not to become involved, and run the risk of losing professional distance.

Ryan:

It has happened, and it is challenging, but we try to make sure that everyone is comfortable with the way we present each story in an issue, because it’s going to reach thousands of people. We also want people to be proud of the story they tell. We always let people read final edits, so that there is nothing in there that hasn’t been signed off on by the initial author. We’ve had stories about abusive relationships, about other things that people don’t usually talk about, and it’s important to tell those stories as well. The value of print media is that people with similar experiences can feel less alone, and feel more okay, because they are reading it in a private, individual setting.

We are sometimes very open and loud about our sexuality, and we often focus on the community. Print allows for a more meditative experience that allows you to look in and out at the same time.

Jonas:

I saw that you recently posted a quote by Penny Martin, the editor-in-chief of The Gentlewoman. She said that working in print builds stronger, more desirable relationships than online. Is that why Hello Mr. is so successful?

Ryan:

I really believe that, and I agree that there is something that binds people together through tangible things. If you see someone reading your favorite magazine at a cafe, you’ll feel an instant connection to that person. When someone posts the cover of a magazine on Instagram, that becomes a statement about themselves. It’s like a symbol, or a badge. For a community that relies on symbols, like the rainbow flag or the pink triangle, to tie its members together, I think that Hello Mr. helps a new generation to identify with one another. Magazines can become a part of your physical environment. It’s part of how you curate your identity. It’s much more tangible.

Benedict:

I think you need a lot of courage to create a gay magazine, but I think you need a lot more courage to create a print magazine in the age of the internet. To me it seems like you are fighting against a restless world, trying to restore meaning and value to time. You give time more significance. Would you say that that is a reason why Hello Mr. is what it is?

Ryan:

I would say so. That’s also why the magazine is biannual. We give ourselves room to publish articles on topics that need not be especially current, and that gives us time to explore events from a different angle. Online media is all about sharing information, and getting comments. That puts a lense of someone else’s opinion on it. That doesn’t exist in print. Other people’s opinions don’t hover over you. That makes it easier to have a direct and undistorted conversation with your readership. They might discuss it later but first it’s focused and quiet.

Jonas:

It’s like an electronic cleansing.

Ryan:

Yeah, and it lets you step out, and have a break.

Jonas:

In your second issue you wrote about your experience as a paperboy, and how it taught you the value of work. A year ago you were picked up by the Barnes & Noble bookstores. Was that a moment that you felt your hard work had been recognized.

Ryan:

To an extent. The work never really stops though, because now there is more pressure to continue growing and reach more people.

Jonas:

The world of capitalism still exists.

Ryan:

Yeah, it’s a cycle. The ambitious entrepreneur’s curse. A lot of people want to see it succeed though, and that motivates you.

Ryan Fitzgibbon is a designer and publisher living in Brooklyn, New York.